The American empire’s wars from 2001 to 2008 were wars of hubris. After 2008 there would be wars in anger. Gaza (that we come to in the next article) is a war against a pocket of resistance to imperial plans (see last article) waged in vicious anger. This article sets out the problem of the empire and starts with pre-2008 background.

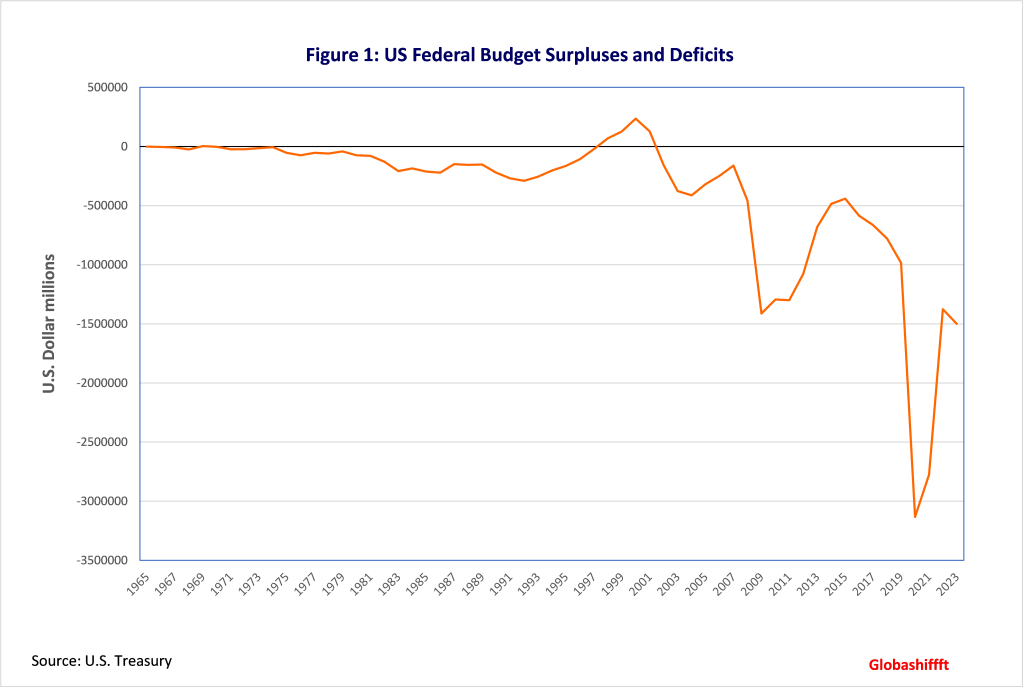

There were four planks to American claim to unipolar dominance in the new millennium. The first was fiscal. After the sharp reaction to the Reagan deficits in the 1992 presidential campaign, Bill Clinton’s win, and the pressure from the Gingrich “Republican Revolution” of the 1994 mid-term elections (foreshadowing Donald Trump’s right-wing populism), the Clinton administration had the (unusual) Congressional support to take the Federal government into its first surplus since 1948. By 2001, the Federal government would register a record budget surplus. See Figure 1.

The second was monetary. James Baker, as Ronald Reagan’s Treasury Secretary had resolved the question of the strength of the Dollar (its trade-weighted index almost doubled from 1980 to 1985) that had given the Japanese unparalleled dominance of the US consumer electronics market. While the 1985 Plaza Accords brought the Dollar back down to where it had started its mountainous climb, it took a considerable while nevertheless for it to sink in that Japan was not going to become the world’s unchallenged economic superpower. As the Cold War ended, the pervasive feeling was that such a new world order as would arise, would do so based on economic rather than military power. But America reeled in shame in Reagan’s last years. Mitsubishi purchased the Rockefeller Center, Sony purchased Columbia Pictures, and Reagan went on a speaking tour of Japan for a fee of $2m. Some of the most strident criticism of American decline was to be found in the pages of Trump’s Art of the Deal.

The third plank to America’s new claims would be a new techno-nationalism that erupted around the bid by Fujitsu for Fairchild Semiconductor in 1986. The American electronics industry had hollowed itself out by outsourcing production to factories in East Asia. Suddenly, however, a group of companies led by IBM, Intel and National Semiconductor ganged together in a desperate attempt to save their dwindling businesses. They brazenly betrayed their avowed individualistic Californian ideology and demanded millions in state aid, exemption from antitrust laws, as well as special protections. The Pentagon responded with an urgent report complaining about the unreliability of its suppliers of electronics components, and the loss by US firms to unspecified “foreign powers” of the military electronics market. The report ended up recommending an initial $2bn revitalisation fund for those firms, and potentially also a state take-over of some areas. Without this state capitalist commitment Santa Clara Valley’s fruit orchards would not have turned into the silicon groves that would come to topple Japan’s technological dominance (to the total surprise of Japanese executives).

The fourth plank of the claim to unipolarity was a renewed but, more especially, a qualitatively altered military power. The digital revolution in weaponry that had been pioneered by William Perry was put on display in the 1991 Gulf War (“Desert Storm”) as American power took on a new invincible-cum-surgical face. This was leveraged into a post-Cold War neoconservative doctrine advocating an American unipolar world order with a humanitarian face. The new doctrine contained in the 1992 strategy paper Defence Planning Guidance for Fiscal 1994- ’99 (DPG) commissioned by Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary, and written by Paul Wolfowitz, Undersecretary for Policy, stressed the ‘moral influence’ and ‘cost effectiveness’ of America’s security umbrella for the majority of the world’s regions. There was no mention of Israel in the DPG, except in the context of a potential peace process between Israel and the Arab countries now that Iraq’s apparent ambitions had been contained.

This changed towards the end of Clinton’s first term in the context of several pressures domestic and international, pecuniary and electoral, that built up behind demands for an expansion of NATO. William Perry, who succeeded as Secretary of Defense in 1994, held his famous “Last Supper” meeting with weapons manufacturers to warn of massive cut- backs in Pentagon orders, now that the Cold War had ended. Bruce P. Jackson, a Defense Department staffer, joined the newly merged Lockheed-Martin giant as Vice-President for Strategy and Planning. He would form the US. Committee to Expand NATO (later renamed the US. Committee on NATO) with Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle (Wedel 2009: 26).

At this juncture, in 1996, Perle, a close associate of Wolfowitz, issued a report called A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm that sought to reshape the Middle East through Israel’s auspices with a focus on régime change in Iraq (289). Cheney, Wolfowitz and Perle represented the core of an association of neoconservatives with close personal ties that would openly seek to shape foreign policy around their personal interests, very often being sanctioned or fired as a result, but always helping each other out as they zig-zagged through different roles in different administrations [This survival strategy is what explains an inability to rid ourselves of neocons, that in Tucker Carlson’s words makes them ‘bureaucratic tapeworms’].

NATO’s expansion occurred even as Europe sought to forge a post-Cold War future with the launch of a new currency: the EURO. This, it was intended by its proponents, would compete on the international stage with the Dollar. However, it soon became clear, during the Balkan War in 1999, even as new East European countries joined NATO, that the United States was forging close security and military relationships with these ex-Warsaw pact nations, specifically in order to secure its control over the major West European states in the EU (Gowan 1999). Later, the events of 9/11 led to major wars in the Middle East that followed the plan set out in the Clean Break report. That series of wars (Iraq, Afghanistan) made people like Cheney rich. They would ultimately end in President Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, with the extraordinary instant evaporation of the Afghan army trained by the US to hold the fort, and the coming to power of the Taliban. The Balkan war and these Middle East Wars were the “wars of hubris” that seriously undermined America’s economy.

I. The Great Financial Crash of 2008 and the End of Unipolarity. By 2003 military adventure would drive Federal deficits to 1.8 times the level of the worst Reagan deficit. Even on the eve of the Great Financial Crash (GFC 2008), these figures only recovered slightly to equal that number. Subsequently, the bank rescue package of 2009 drove the deficit to 6 times, and the COVID pandemic to over 12 times that same number. See Figure 1 again. It is important to remember that the Reagan deficit had been serious enough at the time to cause a political revolution in in the United States in the 1990s (the “Republican Revolution” of 1994). So what happened in the new millenium? The deficit numbers are staggering. The chart looks like an iceberg breaking off from an ice sheet.

What happened was the catastrophic implosion of Wall Street. The 1970s neoliberal turn established the Dollar as the world reserve currency on the basis of the US balance of payments deficit on the current account. This meant that money had to flow into the country on the capital account to finance the deficit and that Wall Street was responsible to create the investment opportunities to allow that to happen. In other words, it had to create sufficiently high returns on investment to attract the capital that would keep growth up and unemployment down in the US. The GFC 2008 resulted from the fact that Wall Street messed up this “brief”. And it did so in stories of unrepentant personal greed that paralleled in finance the egocentric behaviour of the neocons in politics.

But there are two background questions to be answered first before going on. Let’s build up the picture from the ground up…

(i) First: why was it that American imports always exceeded exports to cause the massive deficit?

(ii) Second: how could anybody think that a rich country like the United States could possibly offer sufficient returns to attract capital away from poorer countries. The underdeveloped economic state of poor, developing, or emerging economies – whatever they are called – in the normal course of events, usually promise the highest returns on capital. Where economic theory, therefore, predicts “downhill” capital flows from rich to poor, we came to see the strange phenomenon, instead, of reverse, “uphill,” capital flows funding the US trade deficits. How did that happen?

(i) What have US trade deficits to do with the “neoliberal” turn and what is neoliberalism really? This is a really important historical legacy that needs to be spelled out. The neoliberal turn is supposed to be about applying a system of “free markets” in the economy. This is a myth. There are no “free” markets. The economy is a set of soft (norms) and hard (physical) institutions designed in the interest of one or other social constituency. The neoliberal order is about the (i) rule of the rentier constituency but also (2) about the rule of the rentier as a globalist élite. The “rule” of the rentier is political rather than economic. This is why among corporations banks are dominant. Rather than simply managing the economy’s assets to give rentiers their returns, they create new claims on the economy that continuously reallocate power between different constituencies, between different sectors and between different firms, depending on politics. Under this régime banks became free to grow, to produce all kinds of private money, and move money around the world, all as they deemed fit. This was an extraordinary licence to give to any corporations, given the power involved in creating money. But banks saw the way cleared for them. From January 1974, capital restrictions were lifted, from 1982 regulations on interest rates were lifted, from 1995 limits on mergers and acquisitions and on branch banking were lifted and in 1998 banks could merge with every other kind of financial institution and use depositors money for trading for their own account.

The other thing the neoliberal turn is associated with is the Nixon “shock” of 1971 when the United States stopped converting Dollars for gold, forcing all other nations to use the Treasury bonds, which the United States uses to fund its Federal Budget deficits, as the monetary base for their economies, instead of gold. US Treasury bonds had been proxies for gold. Now they were the real deal. This change created the “Dollar empire.” The Dollar had been important, but now things were qualitatively different. When the US government borrowed, this equated to forced lending to it, by other nations. This is the “tribute” the empire extracts. Too much borrowing sending the Dollar value down would simply be the problem of the empire’s vassals. If the US inflated, and they didn’t want inflation, they would have to restrict credit in their own countries, causing unemployment. That is one of the basic reasons for the “uphill” capital flows underscoring the Dollar empire. The discussion will come back to that in the second point.

“Free markets” are also a myth because the corporations producing goods and services are run like dictatorships. The globalist rentier élite that own them, are able to a large extent, and specifically because of their international alliance, to determine the political environment. Their global aim here is to keep wages and salaries down, and in this they are helped by neoliberal economists that push the “free market” as a valid notion about how economies work. In Universities, they created the language of economics that everybody would use in the world of government and business. In that language, money had no substantive role and banks, therefore, according to that language, couldn’t determine society’s power structures, as they in fact do. Corporations also had no power according to this language, either. They were assumed to be no different to the average street vendor. These aspects of the economic language was subliminal (hidden assumptions). What would be specifically articulated, however, by economists in the late 1960s and early 1970s (e.g. Milton Friedman, Robert Lucas etc…) was that there was no such thing as involuntary unemployment (or underemployment). This meant that people could always find a job if they wanted to and that it was their fault if they didn’t. Unions were said to be unnecessary and inefficient, therefore. This was in tune with the “free market” political ideas of this period.

The political action had begun with corporate pressure groups forming the Emergency Committee for American Trade (ECAT) in 1967 and the globalist Trilateral Commission of 1973. In 1971, the unions (through the AFL-CIO) had proposed a series of measures (in the so-called Burke-Hartke Bill) to protect American industry and force the rentier class and their managements to invest more in their factories to meet the challenge of foreign imports. Ultimately the corporate community defeated these moves and, in passing the Trade Act of 1974, acquired the legal framework within which they could move abroad and seek out cheap labour destinations on terms convenient to them (that would ultimately be enshrined in the “rules-based order” of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and other subsidiary bilateral free trade deals). This would undermine the negotiating power labour had in the United States with respect to wages, workplace rights and welfare. A huge transfer of wealth from labour to capital took place as a result. So we come to the main consideration under point (i). Because these American corporations would go on from there to produce much more abroad for their own market, than they would at home in the United States, the outcome would be a trade deficit.

But actually the corporate pressure groups that managed to pass the Trade Act of 1974 against much opposition in Congress could do so largely because the die had already been cast. American foreign policy elites, along with the US Treasury and Wall Street, had been planning for an American commercial empire, which the Council on Foreign Relations called the “Grand Plan,” as early as 1940. That was the time when they saw the writing on the wall for Britain’s imperial role. These elites wanted to replace the British empire and gain influence over French and other West European colonies. The White House and the State Department therefore pursued an extraordinarily indulgent trade policy in the post-war era, in regard to countries like Germany and Japan, turning a blind eye to their protectionism, while at the same time reducing obstacles to their exports coming into the US consumer market. The idea behind this policy was supposedly intended to avoid communist expansion, and the election of socialist governments in those countries. They wanted to keep them within the American sphere of influence. Japanese and European governments actually also exploited these contrived American fears to their own advantage. The protectionism that resulted from all of this led US corporations to start subsidiaries in Europe in order to be able to operate behind the tariff walls and sell in local markets. This was not possible in Japan, where there was stubborn resistance to foreign companies operating. So the dynamic of exporting to the US consumer market from production bases abroad was a policy followed not only by foreign states but also American corporations, from an early stage. In fact all this would end up contributing as much as the government deficits resulting from expenditure on the Vietnam War, to Dollar weakness and the Nixon “shock.” The year 1971 thus saw the first trade deficit for the United States since 1893.

(ii) How did “uphill” capital flows then happen? Clearly, profits could be made by exploiting cheap labour across the world and exporting to the US consumer market. But this trade gap had to be financed in such a way as to maintain a high value for the dollar to guarantee the profits accruing on these exports. There had, therefore, to be “uphill” capital flows in this neoliberal topsy turvy world. The massive growth of banks and the other financial institutions (shadow banks or hedge funds) that form a hierarchy above (and based on) the banks, would be predicated on the need to mediate the imbalances in this disordered world. There are five points:

- In the initial period of the neoliberal turn, specifically during the two Reagan administrations, wages were crushed and unions broken up, creating opportunities for greater profitability for entrepreneurs in the United States, driving up investment and capital inflows. But many firms still left the United States for greener production pastures as European and then East Asian nations competed aggressively for a share of the exports going to the growing American consumer pie.

- Where firms began outsourcing their products and closed down factories in the United States, this did not apply to non-tradeable goods, such as real estate, health, education etc… Businesses in those sectors maintained high profits even as wages and salaries stagnated. They were able to do this because the average consumer could now access cheaper tradeable goods coming in from abroad (e.g. food and clothes) were cheaper. Wall Street would still “financialize” the non-tradeable sectors, allowing the corporations running them to leverage their assets (chiefly commercial real estate, hospitals etc…) with newly created debt in order to drive up profitability and squeeze the consumer for as much as possible.

- Wall Street (which is short for the financial sector and includes the City of London) did also make “downhill” investments to poorer “emerging” economies. But it did so on a short-term basis, seeking to create bubbles, sending walls of newly created money into those smaller economies, wherever opportunities existed for quick profits (i.e. selling out of the artificially created boom to cash in on capital gain). In this way, higher returns expected from investing in poorer economies could thus accrue in the shorter time frames required by modern financialized operations (so-called “impatient finance”). Long term direct investment (FDI), on the other hand, would be associated with the highly profitable production units of multi-national corporations outsourcing. All these kind of earnings for Wall Street come under “net international investment income” in the current account on the balance of payment. They are important for the highly banked countries that run the Dollar empire (like the US and the UK) and, for them, this is a positive number that offsets a great deal of their trade deficits in goods. This can take place because these countries’ external assets far exceed their liabilities, and because the return on their foreign assets is higher than the costs they incur on their liabilities (being as they are backed by cheap money from the Federal Reserve).

- There is an important point with regard to the “boom and bust” short-term bubble tactics (sometimes called “hot” money flows) which Wall Street uses to make profits in the poorer countries. Official governments and central banks in those countries would decide to pile up Dollar reserves as insurance against these disruptive movements. This was especially important because local entrepreneurs selling into the US market, always borrow to run and expand their businesses, and they would always do so in Dollars. So many are squeezed when the Dollar rises on the back of sudden capital outflows and so their central banks have to be ready to back them up if necessary.

- As the export-led growth model became institutionalised in countries like Germany and in the East Asian economies, including Japan and China, vested interests developed in each local setting. They would seek to keep local currencies cheap and the Dollar expensive, in order to maximise their revenues and their profits. This added to all the factors that ensured constant “uphill” capital flows to the United States.

II. The waning of the neoliberal world disorder, and the China challenge. The GFC 2008 was, on the surface, caused for the same reason all financial panics are caused, namely that, in a decentralised financial system, a number of parties to the system would fail to pay as promised, thereby causing a significant chain reaction. The fact that credit is essential to all markets and that stock is purchased on margin makes complex payment obligations dependent on stock prices, thus leading to a cumulative problem in a downcycle as one failure to pay leads into another. Since the GFC 2008 and since the rescue by the Federal Reserve which, in addition to the government bailout, extended swap lines to banks and central banks all of the world to the tune of $29 trillion, things have changed. Stock market indices have climbed further than they have ever done, despite low growth. This became possible because of stock market investors would no longer look to the real economy for guidance. They just bet that every time the market went down the Fed would support it (in the language of options, the so-called Fed “put”). This has skewed market signals and caused a problematic bubble.

Yet there is a serious problem of dislocation inherent in the fact that Wall Street is itself unable any longer to engineer the necessary magic to make “uphill flows” work. The GFC was catastrophic. The collapse didn’t occur because of unrealised expectations about the economy. Nor did it happen because of false beliefs about the magic that new technologies could impart (as in the case of the internet in the bubble of 2000, or indeed radio in 1929). On the back of computerised finance and their increased political power, Wall Street operators would create “derivatives” as new forms of private money. They did so mostly using mortgage loans (but also using stocks, bonds, commodities, corporate loans, leveraged loans, student loans, automobile loans, commodities, interest rates and foreign exchange rates). The derivative “derives” its value from a complex equation relating these assets together in one form or another, in order (supposedly) to engineer lower risk with higher returns for the investor. For a while capital flows to the United States from the rest of the world boomed on the back of all this new money. When the GFC 2008 finally happened, it would be the first time in history that a financial market crashed, not because the price of a paper asset wrongly anticipated the way the real economy would turn out, but actually because the paper assets themselves were bogus.

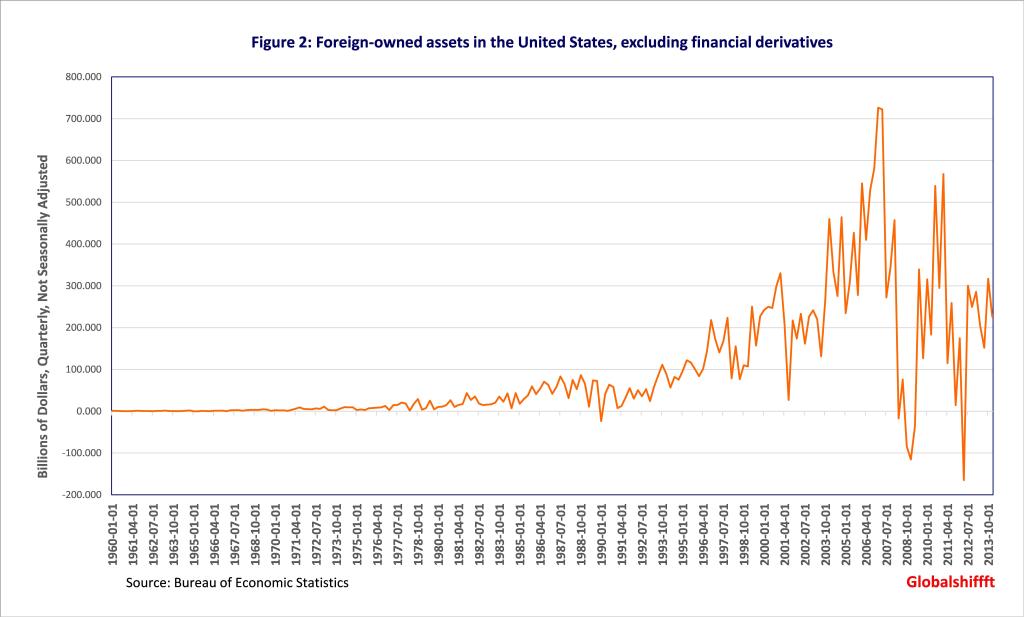

As a result of this debacle the world stopped investing in the United States and Wall Street lost its power to attract the capital funds on the return leg of the neoliberal trading system. Figure 2 shows the gradual rise of foreign investment in the United States from the 1980s onwards and the devastation caused by the GFC between 2008 and 2014, with the chart showing extreme volatility with a clear descending pattern and reducing inflows.

How is the neoliberal system to be fixed? Well it isn’t. And if the solution can’t come from the capital account side, it must come from the current account side. Obviating the need for increased capital inflows, the only way forward is to “reshore,” i.e. to bring the industries back home that could reduce imports, increase exports and bring down the trade deficit, so creating the employment and growth in a virtuous circle that would in turn provide the tax revenues necessary to reduce the US government budget deficit.

This is at least the theory behind the Biden Administration’s plan with respect to the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and the Chips and Science Act. If we factor in the 2021 legislation in the COVID-related American Rescue Plan and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act). This totals to a massive $4 trillion stimulus that involves a state capitalist reindustrialisation project that, by the way, leverages the idea of “decarbonisation,” not for its own sake, but as a way of “climbing over” the problem of global overcapacity and falling economic growth by creating a new leading sector. The idea, therefore, in theory, is that this programme isn’t contributing to the global industrial overcapacity that the world is suffering from and that is threatening recession. But this isn’t a true new leading sector, similar to the digital and internet revolution of the 1990s because it isn’t consumer based. *Rather it is state-directed industrial policy (Tesla is only were it is because of vast state subsidies) that is seeking to replace existing products with ones using different energy sources. The subsidies are not going to be repaid from growth in tax revenue generated by growth in GDP, they need instead to be backed by raising taxes in the first place, much more than the current legislation has allowed for. This will add monetary sources of inflation to the pressures and dislocations of industry retooling, while inflation itself will be recessionary as consumers pay the price of the policy.* [*-* section added]

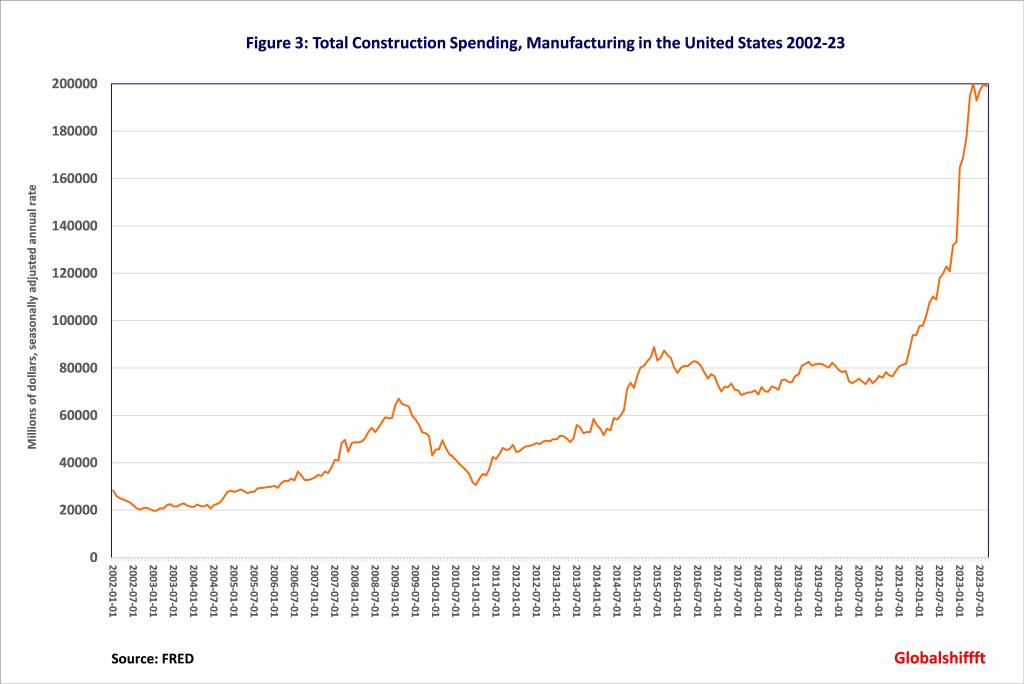

What we can say, however, is that reshoring is happening. Figure 3 shows an unprecedented and sudden rise in the construction of factories in the United States.

At the heart of this anti-neoliberal post-Keynesian programme, however, especially when it comes to the Chips and Science Act, we find an overt attack on China in the “decoupling” implications of reshoring. Much has been made of the preference of the EU (Ursula von der Leyen) for the more diplomatic sounding “de-risking” term. Ultimately, it comes down to the same thing: divorce. But undoing the symbiotic relationship between Chinese export-led development and US over-consumption known as “Chimerica,” this is no easy thing. In fact, it is well-nigh impossible under current conditions.

The solution that America pursued in the case of Japan in the previous state capitalist-led creation of Silicon Valley in the 1990s is not possible. That policy had been predicated on James Baker’s successful negotiation at the Plaza Accords of the revaluation of the Yen (= devaluation of the Dollar). In the case of China, however, this has not been possible. Unlike Japan, China is not conquered territory and thus doesn’t host any US military bases. Hank Paulson, as US Treasury Secretary, nevertheless had actually begun negotiations for the revaluation of the Renminbi with the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao government. However, just as he began the negotiations, the GFC 2008 happened. Paulson found himself pleading with the Chinese instead, for help on stabilising American financial markets.

From the Chinese point of view in fact the GFC 2008 augured the end of capitalism and a new era of socialism. The Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao government faced with catastrophic declining demand for exports enacted a $600bn stimulus package in 2009 to reboot growth, as the world plunged into the Great Recession. These events were fateful in that in one fell swoop the source of value added in manufacturing for the domestic market (as opposed to export markets) for China, which had been at 42.5%, jumped almost immediately to 55% – and has stayed there ever since. Furthermore for the period 2008-2019, which once again comes in the wake of the stimulus package, export of actual value-added rose further to 11.5% while domestic value-added rose much more to 16%. It is these events that Xi Jinping’s government has translated into a plan for a “dual circulation” economy that reduces dependence on the world markets, thereby achieving greater total value-added that is sourced (i.e. that is sold) locally, in addition to achieving greater actual value-added – chiefly though making higher technology products – that are made locally.

The framework that would allow such a radical programme for change was once again inspired by the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao government with its new more aggressive foreign policy (which Hu announced in Marxist terms as the policy of “Actively Accomplishing Something”). Xi Jinping’s government had by September 2013 translated this policy into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI would plough China’s surpluses into infrastructure development in the countries on China’s periphery and the Global South allowing China to downstream low value added industrial production to these countries. In turn, such earnings as those peripheral countries earned, would provide a new source of demand for higher value added high technology goods and services that China would export instead.

This Chinese quest to reshape the world order in this way, rather than revalue its currency and stay within the system has upset the Americans. The James Baker/ Hank Paulson type of “rebalancing” could never work in China’s case, however, even if conversations had started on the revaluation of the Renminbi. The dream of the Clinton administration that the “rules-based order” of the WTO would somehow turn China into a neoliberal vassal state was delusional. For all the “opening-up” talk of Deng Xiaoping, which started China’s career in the neoliberal world disorder, he clearly opted for a socialist state when in 1989 he denounced the students at Tiananmen as “traitors” to the cause and when he called Gorbachev “an idiot” for his political reforms.

It was the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao government that took the reins from Deng’s helter-skelter legacy pursued by the previous Jiang Zemin-Zhu Rongji government, consolidated the state sector upon taking power, and then launched the National Medium and Long term Plan for the Development of Science and Technology 2006-2020 (MLP), which stressed the need for indigenous innovation, eventually doubling R & D expenditure.

The outcome of this strategy was growth by rapid acquisition of new technologies, playing the catch-up card to the fullest possible extent. When China joined the WTO in 2001 all large US corporations developed manufacturing centres in China’s free zones, from where they exported to the United States.

More importantly, they could also sell from there into the fast growing Chinese market. This trump card allowed Chinese negotiators to insist on Chinese partners for all ventures selling into China, and most especially to insist also on the mandatory transfer of technology to those partners. The result of this technological transfer was to create a generation of new Chinese companies that were rudely competitive on world markets and would, within a year of the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao government coming to power, begin to take market share from foreign companies, as can be seen in Figure 4.

The corporate lobby in the United States had always lobbied on behalf of China in the period up to 2009-10. Thereafter, as competition from Chinese firms began to make itself felt, a ‘corporate insurgency’ began to amass ‘against Chinese economic interests’ (Wagreich 2013: 131).

This led the Obama administration to launch the new “Pivot to Asia” strategy, first announced in front of the Australian parliament in November 2011, and articulated by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in a Foreign Policy article. Obama’s strategy was to contain China with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal (from which China itself would initially be excluded) to replace the WTO as a new “gold-standard” “rules based international order” drafted by corporate lawyers with experience of China’s behaviour.

But Trump decided to pull out of the TTP on the advice of his Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, who believed China simply didn’t play by any rules. Using Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which had never previously been used, Trump would start sanctioning China and begin a disastrous trade war which actually initiated the period of dislocation, even before COVID hit, that led to the recent period of inflation.

Biden rowed back on many of Trump’s sanctions against which China had raised counter-sanctions that severely impacted US agriculture in particular. Nevertheless, the idea that China somehow stole technology from the United States still pervades Western discourse although, as the United Nations pointed out: ‘China’s determination to assert its right to development has been greeted with a sense of anxiety, if not hostility, in many Western capitals, despite it adopting policies that have been part of the standard economic playbook used in these same countries as they climbed the development ladder (UNCTAD 2018: iv)

It is ironic that Communist China was by far the largest contributor to world growth in the “golden era” of neoliberalism, contributing over 20% of world GDP growth (ahead of the US’s 12%) for 2000-2010 and over 30% (compared with the US’s 8%) for 2010-2020. Since the 1990’s, this has involved the entry into its industrial labour force of some 400 million workers and the lifting out of poverty of some 600 million people.

US and Western multinational corporations moved to China’s free zones to produce cheaper higher quality goods, at a higher profit, being able to do so on a constant and uninterrupted basis. Both the lower inflation and its predictable constancy led to drops in real interest rates in the United States, with the knock-on effects of increased credit demand by businesses and consumers that benefited the finance sector, raising profit rates across the board and the valuations of all types of asset, including housing.

Thus we had the symbiotic “Chimerica” relationship that created great wealth for both countries albeit doing so by holding down wages on both sides of the Pacific. While China used this wealth to create the largest manufacturing nation on earth and now seeks to move into a new phase of consumption-led growth that will produce a more equitable society – in the Marxist terms used in Xi Jinping though: ‘a moderately prosperous society’ – the United States chose to spend this acquired wealth on “forever wars” and on largesse for the rich in two massive tax cuts, the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and the Trump tax cuts of 2018 that are calculated together to have totalled $10 trillion.

No effort has been made to invest in the education and retraining of workers in the United States to meet the challenges of the future. While the reshoring programme pursued by Bidenomics will increase the number factories in the United States and as the number of job openings rise, labour force participation lags considerably, creating a tight labour market that is at the root of inflationary dislocations that we are experiencing today.

Meanwhile, it is not certain that the aim of reshoring aimed at competing with China is working, or can work. Trade with the US at the end of 2022 still stood at record levels, not counting the fact that many ASEAN countries are increasing imports from China at a faster rate than they are increasing exports to the United States. This is because China, being by far the largest manufacturing nation in the world has become an indispensable supplier of 500 crucial internationally traded goods, where it enjoys a 70% market penetration.

III. The empire’s coups and wars in anger, and the future of Gaza. Along with the “Pivot to Asia” strategy for the containment of China the Obama administration was complicit in the 2010 coup in Japan against the Hatoyama government that sought closer relations with China, and complicit in the 2013 coup in Egypt against the Morsi government that sought to demand the rights of the Palestinians which had been agreed at the Camp David Accords between Egypt, Israel, and the United States but never delivered. Its involvement in the 2014 Maidan coup in Ukraine is on tape.

Cold war 2.0 is all about the sense of ownership of Europe, Japan and the Middle East, that America, or rather that its globalist elites, seek to reclaim in their era of decline. We have witnessed a strange expansion of NATO to the Pacific, and pipelines supplying energy from Russia to Germany blown up. If that isn’t an expression of a sense of ownership, it is difficult to say what is.

Merkel had fought tooth and nail for German sovereignty over the Nord Stream II pipeline. Soon after the Maidan coup, on 16 July 2014, she negotiated a potential “land for gas deal” on the fringes of the FIFA Football World Cup in Brazil with Putin. The intention here was to normalise the status of Crimea (annexed by Russia after the coup), in exchange for a massive Russian economic rehabilitation plan and a gas price rebate for Ukraine. Is it coincidental that the very next day Flight MH17 was downed over Ukraine, providing a golden opportunity for the EU to come on board with US sanctions targeting Russian energy deliveries while, in the process, enhancing the prospects for US shale LNG deliveries to Europe?

Actually if we look at the Reshoring Initiative 2023 Q1 Report, the industries and firms attracted by the incentives in the Biden legislative package are coming to the US from the (new and old) NATO countries of Japan, Germany, and South Korea. They are not moving from China. Not even Apple is moving from China. German companies in particular are migrating to the US to reduce their energy input costs, given that landed prices of US LNG as a replacement for Russian gas are excessive.

The Biden administration completed its disastrous pullout from Afghanistan by August 2021. This involved the extraordinary sudden evaporation of a 200,000 man Afghan army which the US said it has trained to police the country on its behalf. Even as the Taliban took over, Biden began warning the world of an upcoming Russian invasion of Ukraine.

This eventually happened in February of 2022, after multiple attempts by the Putin régime to negotiate a neutral status for Ukraine that were routinely rebuffed. The March 2022 Istanbul peace deal signed by Ukraine and Russia was then scuttled by the Americans and the British. If the Ukraine War has not served to topple the Putin régime as was Biden’s clear intention, it has served to maintain Europe squarely under the American thumb and erect a new iron curtain. Ukraine and its people have been destroyed in the process.

This dynamic is not too dissimilar to that playing out in Gaza. After the G20 in New Delhi on 9 September, which Xi Jinping stayed away from, the prospects for the Biden Corridor (IMEEC) from India through the Arab Gulf then Israel (read Gaza) to Europe seemed to be going swimmingly. America was going to circumvent the Belt and Road Initiative. Then Al-Aqsa Flood happened on 7 October and the wrath of empire fell on the enclave. This story I will take up again in the next article. [Ref: Prt 11 Post-Script 14 -3; info@globalshiffft.com; © 2023]

Leave a comment