Introduction

American hegemony and Europe: The Biden-Harris Security Strategy sees China as the central strategic threat to its global dominance. The reason for this is a corporate insurrection beginning in Obama’s first term reflecting the intense pressure many American transnationals face from competition from Chinese corporations. Russia is deemed in the same document merely to be ‘dangerous,’ although in what way isn’t specified. If the document indicates that Russia needs, for that reason, to be ‘constrained,’ the term doesn’t quite describe what is going on in the Ukraine War. In fact, to the extent that the American foreign policy establishment has nailed itself to the mast of NATO expansion as a way of establishing its hegemony over Europe since Bill Clinton’s first term, Russian action in Ukraine looks to be more than just dangerous: it is shaking the very foundations of empire that the US has built up since 1995.

For the US, the Ukraine War is actually less about defeating Russia than it is about keeping Europe under control and its economy, together with its upstart common currency (the EURO), permanently dollarized. Wolfgang Streeck tells us: ‘If there ever was a question of who is boss in Europe, NATO or the European Union, the war in Ukraine has settled it, at least for the foreseeable future.’ This involves an ideological campaign that has regimented a Western mainstream discourse that forbids discussion of the motives of the Russian leadership (equated glibly with Putin’s person) making peace negotiations all but impossible. Any such discussion is considered in Germany a treasonous act of Putin verstehen. Some realists see the Ukraine War as ‘unwinnable’ and demand that the US administration envision an ‘endgame’ (Charap 2023). Other realists view the possibility of such as vision as impossible in the circumstances, and they predict the outcome as a frozen conflict (Mearsheimer 2023).

The doctrine of the US foreign policy establishment dates back to Bush I and his Secretary of Defense, Dick Cheney. Its translation into policy came with Bill Clinton’s expansion of NATO and Madeleine Albright’s sharp turn on the Serbia-Kosovo War, at the time of the launch of the EURO in 1999. When Gerhard Schröder sided with Chirac in 2003 against joining in the Iraq War, Bush II’s Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld made light of the German and French objections. Rumsfeld clearly thought NATO expansion had served to strengthen the hand of the United States against the recalcitrants, when he pointed out that the ‘… centre of gravity is shifting east’ (Van Hooft 2020: 544). When new NATO members in 1999, the Czech republic, Hungary and Poland, as well as prospective future members, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and the Baltic states, backed the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq, Germany and France were forced to eat their words and provide logistical and diplomatic support.

After the Schröder-Chirac objections to the Iraq War in 2003, Jeffrey Gedmin of the US Council on Foreign Relations and Craig Kennedy of the German Marshall Fund of the United States led the way in an ideological campaign against European anti-Americanism. This would be followed by many think tanks and NGOs, such as the Aspen Institute Berlin, Atlantik-Brücke, Stiftung Mercator, the Munich Security Conference (c/o McKinsey & Company), and the Royal United Services Institute [RUSI] in London. In 2003, ahead of her very first election to the German Chancellery, Angela Merkel, also joined in the campaign, attacking Schröder’s anti-Americanism in the Washington Post. Ultimately, thanks largely to Merkel, the primacy of NATO would be secured in 2007 in the Lisbon Treaty, which stipulates in article 42.7 that no European security policy jeopardize commitments to the Atlantic Alliance.

The United States now faces the problem of a resurgent Russian state that has executed a punishing war in Ukraine. You wouldn’t know this from Western media reports. But this article, in its analysis, goes beyond realists such as John Mearsheimer in his latest article on the ‘darkness ahead’ and the idea of a frozen conflict. It suggests that the level of destruction meted out on Ukraine is so great and the realities that are suddenly becoming apparent about the capabilities of the Russian military such that an actual defeat stares NATO in the face. This fact, however it may be managed by the Atlantic Alliance, will have dramatic reverberations across European politics. In fact, the most prescient analysis on this subject came from Brigadier General Erich Vad, Merkel’s recently retired military advisor, who saw imminent defeat on the cards, in other words a ‘war that was winnable,’ but winnable from the Russian point of view. Vad went on, however. He also called this outcome an existential threat to (the US) empire as the scales begin to fall from the eyes of European publics with the news of defeat. This is why Vad, an ex-NATO official, pushed for an urgent peace in Ukraine.

Mearsheimer correctly sets out the basic problem for the United States in this war. It has allied Russia and China and is thus ‘hindering the U.S. effort to contain China.’ Thus we see the basic contradiction in US behaviour that is undoubtedly the most important factor that is bringing about the end of US hegemony. This was emphasised in no uncertain terms in the first introductory video on the Globalshiffft site. Mearsheimer sees China as the true ‘peer competitor’ to the United States, presumably as an economic power. Analysis of the events in Ukraine, however, show how Russia has emerged as a peer competitor of the US on the conventional battlefield, where it counts for Russia, on land rather than on the sea. With the success that Russia has had in navigating the unprecedented sanctions imposed by the United States and the West, it has been able to further reinforce its military industrial capacity. While, with its successful transition to modern mechanical-hybrid warfare, Russia has surprised NATO military planners.

Despite Russia’s deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus on the border with Poland, talk of nuclear war in the Western media associated with visions of a “desperate Putin” is a red herring. The deployment itself is a response to the long-standing US missile defence systems in Poland and Romania. What is relevant is that Russia is not only engaging in what is a very large conventional war, but that it is winning it, as is evident from the failure of the latest Ukrainian counteroffensive. Furthermore, Russia has been gradually and doggedly winning this war from the first “siege” stage of the war that followed the failure of peace negotiations in Istanbul. Nuclear fearmongering is a tactic of the Kiev régime intended to up the stakes in its bid to become a NATO member. In that regard, it has designs on blowing up the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, which is under Russian control, in order to create a “nuclear emergency,” to put pressure on NATO ahead of the Vilnius summit on 10 July. Athough this is highly unlikely to succeed, because of the protective steps the Russians have taken, the US has nevertheless sent a WC-135R aircraft to Spain to detect potential spikes in radiation levels in the event of such an occurrence (2 July at 23.20 mins).

A new area of concern, on the matter of blowback from the war on European politics, is in regard to the apparent plan to involve Poland increasingly in the war, as Ukraine implodes spectacularly. This will have enormous consequences not only for internal German politics but for the relations between Germany and East European countries, as German forces will need to be stationed in Eastern Europe. Early signs that Polish troops are being moved towards the Belarus/Ukraine border are already with us (2 July at 21.56 mins).

The analysis below starts with a discussion of Russian internal politics and the Prigozhin affair, which has, in an extraordinary turn of events, served to strengthen the Kremlin’s hand in the conduct of the war. Part I covers this and the various stages of the war. Part II covers three background factors for those who wish to read on to discover: (i) how Russians view the dissolution of the Soviet Union and why they have been united behind Putin’s state building project; (ii) how Putin views his state building project in terms of energy policy and how this has determined his narrowly-focused foreign policy, including his policy in Ukraine; (iii) how the US foreign policy establishment alienated Russia through its various phases of NATO expansion as a policy really intended, especially in its early phase under Bill Clinton, to keep Europe under its thumb.

Part I

I. 1. Transformation of the politics of war in Russia, and the Prigozhin gambit: Putin and the Russian leadership have faced stiff internal opposition from the nationalist current critical of its slow and deliberate pursuit of the Russian state’s interests in the prosecution of the Ukraine War. Where Putin can be said to espouse nationalism in the sense of ‘state patriotism,’ radical Russian nationalism, which among other things believes in Russian ethnic purity, has been an enemy of the state since the 1990s (Sakwa 2020: 61). The most recent example of its opposition is the failed insurrection on 24 June of one of their heroes, Yevgeny Prigozhin. It has been suggested that Dimitri Utkin, Prigozhin’s second in command in the Wagner group is a closet neo-Nazi. This Russian nationalist sentiment against the country’s leadership had been inflamed as far back as 2014 by Putin’s refusal then to: ‘recognize [the] Donetsk and Lugansk’s referendums, [and that he] did not formally invade Ukrainian territory, but instead worked to keep the rebellious provinces within the Ukraine proper. Those who expected Putin to assemble the historic Russian lands [Novorossiya] were disappointed’ (Tsygankov 2015: 294-5).

What rankled most with nationalists at the time was how Putin was being manipulated in the Minsk I and II negotiations by a Kiev régime that had no intention of living up to their agreements. Would it not have been apparent to Putin and FSB intelligence, which has displayed a formidable grasp of information on Ukraine during this war, that they were being played? Both Angela Merkel and François Hollande would eventually confirm that Western governments had in fact colluded with Ukraine in the deception. This had given the Kiev régime time to build up a formidable army with NATO, more specifically, British, help.

When events eventually conspired to trigger the February 2022 recognition of the Donbass Republics and the military intervention to support them, nationalist sentiment in Russia surged, only to be disappointed once again, however, by the limited nature of the operation. Prigozhin sought to exploit this sentiment and the military victory of his Wagner group in the bloody battle of Atyomovsk/ Bakhmut, to further his political ambitions. After breaking camp, he led some of his troops in a so-called “march for justice” towards Moscow with the aim of rallying nationalists to his cause. The gambit failed. Unlike General Lebed in his rebellion against Boris Yeltsin in 1993, Prigozhin garnered no support at all.

Putin formally charged him with the crime of “armed insurrection,” as opposed to treason, which would have implied collusion with a foreign enemy. Prigozhin faced either a very public trial, if he surrendered, or the equally public massacre of his rapidly diminishing convoy lining up for destruction on the M4 motorway, by the full force of the Russian air force, if he did not. Putin, seeking to avoid either outcome, organized his exile to Belarus with the help of Belarusian president, Alexander Lukashenko. The few Wagner troops that obeyed Prigozhin’s insurrectionist orders were pardoned, although the organisation itself and the corporations behind it on Russian soil have been disbanded.

The Prigozhin episode has brought about political unity in Russia on the matter of the war. The way in which Prigozhin’s actions were met with surprise and disappointment, even amongst avid followers, was remarkable. The political impact this has had on Russian society is akin to somebody suddenly turning the lights on in a darkened room, only for the room’s occupants to realise how many people actually supported Putin’s conduct of the war. Putin at 83% and Lavrov at 76% remain the most popular politicians in Russia according to the Levada Centre, while Prigozhin’s popularity has collapsed. Together with Putin’s war policy, the war machine of the Ministry of Defence in Ukraine has gone from strength to strength after Wagner’s disappearance. However, with fraud and corruption investigations now launched into the affairs of Prigozhin’s Concord and Voentorg companies, this has taken its toll on Putin. In his meeting with the Defence Ministry personnel, he is visibly shaken by the potential for sizeable financial losses, where he says quite frankly that he hopes Prigozhin, Utkin and their Defence Ministry acolytes ‘did not steal a lot.’ This public airing of this matter is intended it seems to bring the full force of public opinion down on those in the military industrial complex who have been paid by Prigozhin for their support. Dimitri Medvedev has added to the hue and cry by saying that all he sees in this matter is a lot of ‘pigs’ snouts.’

I. 2. The narrative built up around the Russian invasion 24 February 2022: Russian forces invaded Ukraine on 24 February with c. 90,000 men. This may sound like a lot, but it is nowhere near the number needed to invade a country the size of Ukraine (=France, or Texas) with close to half a million men under arms, and a core professional army of 260,000 trained by NATO over the period 2014-2022.

Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Milley, in an interview on 2 May laying the ground for the Ukrainian “counteroffensive,” said that the Russian objective in this war had been to: ‘… collapse the Zelensky government; capture the capital of Kyiv, to do that relatively quickly; advance from the Russian border all the way to Dnipro River, do that in a short amount of time, four to six weeks, perhaps; and then also to cut off Ukraine’s access to the sea, to the Sea of Azov, by securing Kherson and Odessa. Very short order—the invasion started on the 24th of February—in very short order, Russia fell short of their strategic objectives, really within about a month or so.’

What is striking about this statement is that it portrays the kind of campaign that the Russian nationalists would have preferred Putin undertake. Milley would have known that the size of the operation launched could not have had the kind of strategic objectives he was outlining. His narrative did allow him, however, to conclude that his antagonist had ‘fallen short.’ Good PR, but misleading.

The Russian government made it plain, from the outset, that it was launching what it called a ‘special military operation’ [SMO] with the intention of “denazifying” (getting rid of the likes of the neo-Nazi Azov battalion in the Ukrainian army) and “demilitarizing” (inflicting losses on Ukrainian weaponry by attrition) Ukraine. What it was clearly not focused on was the capture of territory, whether Kiev, Odessa (old capital of Novorossiya, with symbolic significance for Russian nationalists), or otherwise.

The SMO would actually be no more than a muscular attempt by the Russian leadership to drive the Americans to the negotiating table on a neutral status for Ukraine, where the United States had, up until then, ‘failed to give a constructive response,’ to Russia’s diplomatic overtures. The negotiations that followed the invasion, it has to be remembered, first started in Belarus on 28 February, just four days after the launch of the SMO: hardly a sign that Russia wanted to absorb Ukraine. The view that the SMO was simply “diplomacy by other means” is, furthermore, entirely consistent with the experience of Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, who took the initiative of personally engaging in shuttle diplomacy to try and bring the conflict to an end. Bennett was surprised by the speed at which he managed to negotiate an agreement between Ukraine and Russia on core issues (Bennett video at 2hr 33mins).

Bennett would be equally surprised at the negative stance of the NATO powers, however, especially that of Britain. Boris Johnson, supported by Biden, pushed for war. The withdrawal of Russian forces from the Kiev area, as a goodwill gesture during the peace negotiations, would be weaponised by the US/ UK narrative on the imperialist Russian desire for territorial expansion, as a taunt to enrage nationalist sentiment in Russia. Putin now faced a backlash because as the SMO was ‘a limited operation with a narrow purpose and restricted goals…,’ it actually‘achieved the opposite of the outcome that Moscow desired, conveying the impression of weakness, rather than strength’ (Macgregor 29 November 2022). Putin miscalculated where he believed that he actually had a potential partner for peace, and he was thus made to look weak when the US and the UK rebuffed him. Where he hadn’t miscalculated, however, – what the US and the UK failed to appreciate – was in the ability of the Russian military to turn things around and conduct a successful war in Ukraine and of the Russian economy to withstand sanctions.

I. 3. Russia embarks on the first phase of the war proper: The first phase of the war would be a siege campaign. Ukrainian fortifications had been built using Soviet factory complexes and high rise buildings of massive concrete, enhanced with underground bunkers, tunnels and trenches build up over many years. The belief of NATO leaders that Russian forces would be broken on these defences was, on the face of it, not an entirely irrational hope. Despite these formidable odds, however, Putin resisted domestic pressure to mobilise Russia’s reserves. The US Treasury’s equally formidable trade sanctions clearly posed a problem. In rejecting Putin’s peace moves, the US was essentially gambling that the sanctions would break the Putin government. Putin realised that mobilisation would have created additional disruption in a Russian economy facing unprecedented economic difficulties as a result of the sanctions, and the freezing of all Russian foreign exchange reserves held with the Federal Reserve and other western central banks.

The war therefore became attritive: one in which the local militias of the Donetsk and Lugansk Republics, special units such as the Akhmat (Chechen) special forces, and the private Wagner group (Prigozhin) would be made to take on the brunt of the front line fighting. Despite insulating itself in this way, the Russian army nevertheless played the most crucial role in the process of attrition. Taking fortifications required that front line forces conduct gruelling storming operations on Ukrainian fortifications. Storming operations, however, could only be successful to the extent that they actually were in this campaign, if a selected target had first been extensively suppressed (i.e. pulverized) by artillery and missile attacks. The capacity of the Russian forces to do this surprised NATO and meant that the Russian Ministry of Defence would continually report very high daily losses among Ukrainians despite their formidable defences. Once when questioned by Putin as to the source of these reports, Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu said that ‘they largely came from intercepted information: reports from Ukrainian unit commanders on sanitary and irretrievable losses.’

The NATO think tank, Royal United Services Institute [RUSI], reported on 17 Jun 2022 that 7,176 artillery rounds were spent by the Russian forces every day, adding that ‘US annual artillery production would at best only last for 10 days to two weeks of combat in Ukraine,’ and that the ‘expenditure of cruise missiles and theatre ballistic missiles is just as massive. The Russians have fired between 1,100 and 2,100 missiles… meaning that in three months of combat, Russia has burned through four times the US annual missile production.’ NATO was waking up to the consequences of the massive increases in military expenditure on the modernisation of the Russian armed forces over the two decades since 2000, when Putin took power. In ‘Europe the conventional military balance shifted in favor of Russia… [it should have been] clear to anyone who could read IISS Military Balance that Russia was enhancing its capabilities. (Davis 2016: 275).

I. 4. Russia turns the tables in the second phase and builds a fortified line: The siege phase of the Russian campaign ended with the dramatic fall of Atyomovsk/ Bakhmut to Russian control. A new phase in the war would come with the announcement by the Kremlin of the mobilisation of 300,000 reservists on 21 September 2022, following confirmation that the Russian economy had withstood the impact of sanctions and that inflation, unemployment and growth had stabilised: good news on the economy that, furthermore, would be confirmed by the IMF. A new defensive phase of the war was launched with the appointment of General Sergey Surovikin as theatre commander at the front on 8 October. Surovikin decided to consolidate positions behind the Dnieper river in the Kherson region by withdrawing from its north bank. A Russian Defence Ministry Board meeting on 21 December would then record that the ‘building of fortifications’, had been undertaken in view of the fact that ‘capabilities of almost all major NATO countries are being widely used against Russia…’.

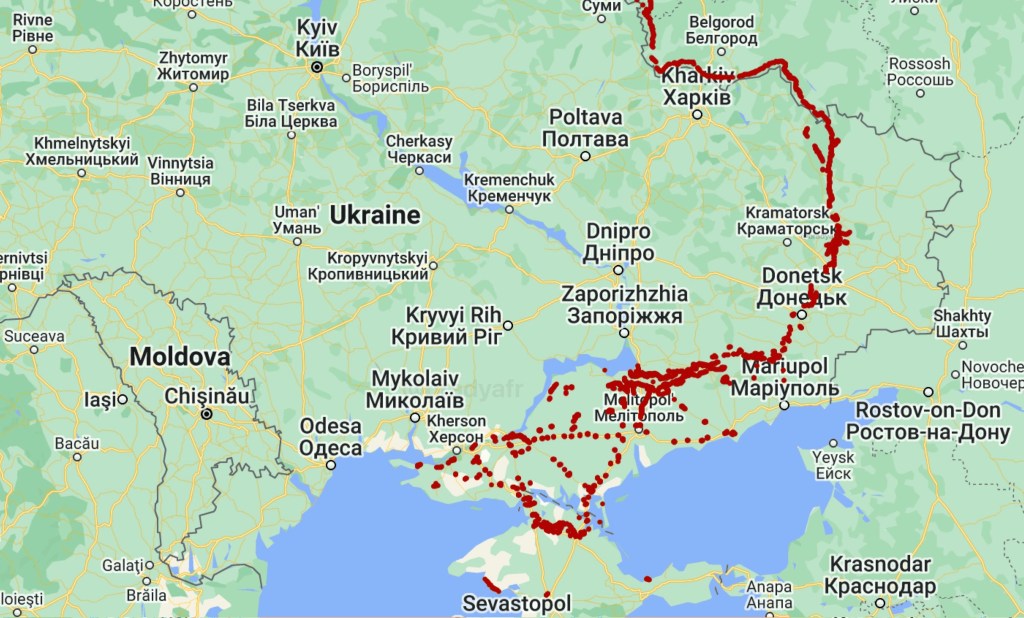

The lead picture above shows the open source reconstruction of the circle of Russian fortifications around the front line. Some 1,500 km or just over half of the overall distance represented by the circle, from the sea west of Kherson all the way to Kharkiv, through the Donbass, represents the active front. A new open source map shows how the Ukrainian fortified lines captured during the siege phase of the campaign now lie within the Russian circle of fortifications, and how, at some points, they are incorporated. RUSI noted how the Russians were essentially preparing a ‘meat-grinder’ in which to drag the Ukrainian army: ‘Russian engineers have been constructing complex obstacles and field fortifications across the front. This includes concrete reinforced trenches and command bunkers, wire-entanglements, hedgehogs, anti-tank ditches, and complex minefields.’ The nature of so-called “complex” minefields, is that they are dynamic and laid and re-laid with distance launchers.

With the surprising success of the Russian first phase and the new phase promising to be much more difficult, Milley broke ranks with official US policy on 9 November 2022, by calling for peace negotiations. He was brought back into line, however, as US President Biden set out to ram a record $858 billion military budget through Congress, round-tripping Zelensky on Air Force One as the supporting celebrity act in Congress, an event presented in the media as the ‘second coming of Winston Churchill.’ The idea was to shower Ukraine with money and weapons and to set out to push Russia back. In his 2 May interview a chastened Milley says: ‘… the Ukrainians asked us for help to build up their force so that they had the capability, anyway, of conducting offensive operations with combined arms maneuver with heavy forces, mechanized armor and infantry. We’ve done that, and we have not yet seen what that’s going to result in…’. He expected to see results in the coming “great spring counteroffensive.”

I. 5. The “great Ukrainian spring counteroffensive”: This actually started in June. When Milley insisted on 5 June that Ukraine was now “very well prepared” for the upcoming high-stakes effort to retake its territory, he could only have been talking for the form, obeying the orders of his civilian bosses, ahead of his coming retirement. The Ukrainian army had no air force with which to support infantry advancing over open territory now towards well prepared Russian defences and, as the Pentagon Papers 2.0 leak had uncovered, as a result of months of massive Russian missile attacks across Ukrainian positions, little or no air defence was left to counter the Russian Aerospace Forces [VKS], which has lain quietly in wait for those air defences to be destroyed. One can only surmise the leaks were the work of Pentagon staffers infuriated with White House policy. Furthermore, unable to counter Russian electronic warfare, the Ukrainian army had neither the means to suppress Russian defences, counter the Russian air force, nor withstand Russian suppression of its own communications.

The counteroffensive started on 4 June. As Ukraine moved newly trained and equipped strategic reserves to the front, they failed repeatedly to advance into Russian controlled territory. Massive attacks on 9 June and the night of 9-10 June fared no better, halting well short of Russian fortifications. A combination of Russian dynamic distance mining, artillery fire and drones kept the Ukrainian army at bay. Carnage continued among Ukrainian troops, estimated at 15,000 killed and seriously wounded for the period up to 22 June alone, with especially heavy losses on 18 June and 21 June, with considerable amounts of NATO supplied equipment being destroyed. at the same time

The counteroffensive having failed, the Ukrainian leadership signalled its determination to continue with the announcement of a total mobilization of the population on 22 June. All this could now do is to burden NATO with the Sisyphean task of training a new batch of raw recruits for a fourth time since the training cycle began 2014, as a dwindling Ukrainian population is put through further unbearable stress, and NATO itself struggles to match the preparedness of the Russian military, and the considerable industrial capacity it has been able build up over two decades across all sectors of the military. This contrasts with the sharp decline in available manufacturing capacity and relevant labour pools and skills in the United States for the production of small arms and ammunition, as opposed to the focus of its defence industry, since the 1990s, on experimental and expensive, very often unreliable, weaponry, the purpose of whose production is simply to maximise profit margins.

I. 6. The turning point in modern warfare: A Modern War Institute at West Point report on 15 June tells us that, although ‘not always portrayed as such, the war in Ukraine is, or at least has become, a peer conflict’ between Russia and the United States. This is because of the extent of Western and especially US support, providing Ukraine with significant amounts of advanced weapons systems—not to mention real-time battlefield intelligence to help identify Russian targets for Ukrainian long-range precision strikes. ‘As a result, this is the first war in history in which both sides are capable of striking throughout the opponent’s tactical and operational depth with a high level of accuracy.’

The West Point report, significantly, attaches the parity between Russia and the United States not to their nuclear (which is common knowledge) but to their conventional capability. This is a crucial point because it is precisely the brute explosive superiority of the Soviet nuclear arsenal over that of the United States, which prompted William Perry as Undersecretary of Defense for R & D under Carter (1977-1981) to devise weapons fitted with microchips, guided by digital technology, that would give American weapons a qualitative advantage over Soviet weapons. This ‘military-technical revolution’ (Cohen 1996) and its computer guided weaponry, provided solutions that would push nuclear weapons and their uncertain military, environmental and political outcomes in a highly interconnected world, firmly into the realm of the unnecessarily problematic, if not of the outright redundant.

The first Gulf War (Operation Desert Storm) prosecuted by Bush I against the Iraqi régime in 1991, saw the very first use by the United States of precision weaponry. Its fearsome successes gave the American political establishment a new sense of invincibility. Not only was the Soviet Union in the process of dissolution but, significantly also, Japanese technological and economic dominance was in decline. This was the political climate in which Bush I’s Secretary of Defense, Dick Cheney, tasked Paul Wolfowitz, Undersecretary of Defense for Policy (1989-1993), to draft a new post-Cold War policy document. The Defence Planning Guidance for Fiscal 1994-’99 (DPG) was issued in 1992, proclaiming a unilateralist sole superpower status for the United States. Neoconservatives, among them Wolfowitz himself, rallied to this doctrine, making it their own. Unilateralism would first be applied in the ‘War on Terror’ grounded in long standing Israeli Likud policy (Netanhayu 1986), because of the close personal links between the Likud and U.S. neoconservatives.

Its application in the Ukraine War, however, represents the first trial of precision weaponry against Russia, as a peer power, in the conventional sense noted above. The West Point report tells us that while the uninitiated media focuses on what appear to be mistakes made by the Russian military in the course of this war, such developments needs to be interpreted in the frame of whatever overall coordinated battlefield strategy is required of any belligerent pursuing modern precision warfare. What is lost in ‘…this simplified narrative… despite the numerous and obvious shortcomings displayed in Russian military forces’ performance in practice…’ is the fact that ‘…on a conceptual level they are actually ahead of their time.’ The point being that, in the new kind of dynamic warfare, failures and successes cannot be assessed on the simple advance/retreat metric, but from the perspective of overall battlefield strategic requirements. The complexity of the situation means, however, that Western media is always free to interpret events on the ground, in a way that bolsters its narrative, but that is meaningless in military terms.

The principal outcome from this new kind of warfare, which has advanced considerably with the use of undetectable all-seeing drones in recent years, is that the concentration of forces that are normally required to effect a successful attack is vulnerable to total destruction when detected. ‘This is reducing large-scale engagements and thereby necessitating a concentration and synchronization of effects, rather than a traditional physical massing of troops. In turn, this places an extra burden on command and control, especially when contested by electronic warfare.’

Operations therefore require an effective command and control with impeccable communications that can bring together many far-flung units onto a particular target on a timely basis in coordination with ‘effects,’ i.e. electronic warfare, setting of fires, and psychological and hybrid action. Assessment usually follows action, feeding back into decision-making, as in the case of a Russian missile strike on Kramatorsk on 28 June, which was followed by a video assessment that detected English being spoken, while showing the arm of a US soldier sporting the tattoo of the Third Ranger Battalion, who was found to be among the throng of rescuers attending the wounded. That particular precision attack killed several Ukrainian army leaders.

The most worrying thing for NATO is less the ramping up of military production in Russia as such, and more the rapid evolution and improvement of Russian command and control as it adapts over the course of the war and plugs crucial gaps. It is fast improving the quality of its radios and ‘battlefield-centric integration systems’ that coordinate timely battlefield messages. It is also developing and adapting Iranian drone technology (with direct Iranian collaboration), and remedying the shortage of military satellites, as can be seen in a recent conversation between Putin and Yury Borisov of Roscosmos, the space agency.

So what the West Point report considers to be the advanced conceptual nature of Russian military doctrine is being brought into practice for the first time in a high level conflict arrayed over a front exceeding 1,500km, and testing command and control to the limit. NATO had expected Russia to fail here. But if it is practice that makes perfect, and it is NATO that is patently failing, then the Russian military appears to be passing the test and evolving into an unexpectedly formidable opponent in land-based warfare.

Part II

II. 1 Why the Russian political classes don’t consider that the demise of the Soviet Union was caused by action by the West and why they backed Putin in his resurrection of the vertical power of the state:

The fundamental misconception that underlies NATO triumphalism, lies in its claim, made in May 1993, to have won the Cold War ‘without firing a shot’. This is a ridiculous statement to be made by a military organisation, which should normally gauge success through actual military engagement with an antagonist. But even if the US Budget could be blown out of all proportion because of the extraordinary privilege the dollar enjoyed as a reserve currency, there would still be severe political repercussions in the United States. A phase of retrenchment followed, catalysed by the participation of the third party candidate, Ross Perot, in the 1992 presidential elections, on a ticket that sought sharp reductions in the government deficit. Newt Gingrich picked up the baton from Perot and led the ‘Republican revolution’ in the 1994 mid-terms that would hound the Clinton administration for the duration.

Even if the Soviet Union had overspent on the military, this was nothing new, and wouldn’t have led to the collapse of the Soviet state’s finances and its dissolution, if it hadn’t been for the convergence of a number of purely internal factors that brought down the Russian state. Chief among these factors, most Russians would be quick to point out, was the stupidity of their chief reformer, Mikhail Gorbachev.

It would be precisely those reforms intended by Gorbachev to remedy the Soviet Union’s systemic ills that led to its unravelling between 1987 and 1991. In a system that was designed to maximise capital goods production, a legacy of informal networks in the bureaucracy had developed to compensate for the inability of Soviet system to cater flexibly for the production of consumer goods (Grossman 1998: 24-50) .

New freedoms given to enterprises in Gorbachev’s misconceived managerial reforms (perestroika) failed crucially to address the necessary corresponding property rights, and this led immediately to cadres improvising a response to the new directives through their pre-existing informal networks, with a resulting explosion in what has been called ‘spontaneous privatization’ (Johnson 1991). This unravelling of vertical chains of command occurred also in the administrative system between regions and a centre that began to experience severe financial difficulties. As Communist Party leaders could no longer control their subordinates or make sense of the reforms, they revolted. Meanwhile some political entrepreneurs, like Yeltsin, decided to challenge the whole system rather than support reform: not at all what Gorbachev had intended for his policy of political “openness” (glasnost). This describes, more or less, the de facto dissolution of the Soviet Union.

If Gorbachev is considered by the majority of Russians today as an ingenu who needlessly destroyed the USSR, their visceral hatred of him is more to do with his foreign policy. Gorbachev sought to end the Cold War by offering to withdraw from Eastern Europe, and to attract the UK, France and Germany away from the influence of the United States, befriending Thatcher, Mitterrand and Kohl in the process to ‘build a common European home.’ Gorbachev’s designs, however, were upended by Kohl’s taurine drive to reunite the two Germanys, now that the communist German Democratic Republic [DDR] was in free fall. This brought the United States back full square into the European action. James Baker, Secretary of State to Bush I, previously Reagan’s Chief of Staff and Cold warrior par excellence, manipulated Gorbachev into accepting a reunited Germany within NATO with his ‘not one inch eastward’ hypothetical in February 1990. Would the Soviet Union really want a reunited Germany to realise Hitler’s dream of an independent nuclear weapon, he asked? Wouldn’t it be better if Gorbachev agreed that NATO stayed on? If he did, NATO wouldn’t move east ‘an inch’ (it would be Germany’s borders that moved) (Sarotte 2022: 55).

Be that as it may, military chief Vladimir Kryuchkov, and KGB chief Sergei Akhromeyev, were outraged at their leader agreeing to give up Russia’s legal right to keep forces in Germany without so much as a written contract. The Americans had to rely on Gorbachev’s more flexible foreign policy advisor, Anatoly Chernyaev, to keep Kryuchkov and Akhromeyev away from Gorbachev during the negotiations. In the event, Gorbachev was subject to a coup attempt at his dacha in Crimea in August 1991. This failed when Yeltsin rallied Moscow against it. But Yeltsin’s stab in the back would not be long in coming. In the Belavezha accords with Ukraine and Belarus that he instigated, three of the four founders of the USSR (the Transcaucasian SFSR no longer existed) met in secret on 8 December 1991, to end the union. This represented the de juro dissolution of the Soviet Union.

II. 2 Why Putin rebuilt the Russian state, how he did this by focusing on energy policy and how this influenced his initially limited approach to the war in Ukraine:

Putin watched from afar as the Soviet Union foundered, and as the DDR, where he lived and worked as a KGB functionary, fell headlong into the Western orbit. Gleb Pavlovky, a close political adviser to Yeltsin and then to Putin, until 2011, relates what Putin and he both felt at this self-inflicted dissolution of ‘the great state in which we had lived, and to which we had become accustomed…. My friends and I were people who couldn’t accept what had happened: who said we can’t let it continue to happen. There were hundreds, thousands of people like that in the elite, who were not communists… This group consisted of very disparate people, with very different ideas of freedom. Putin was one of those who were passively waiting for the moment for revanche up till the end of the 90s’ (Pavlovsky 2014: 56).

The severe financial difficulties that followed the refusal of the regions to repatriate taxes to the centre caused a potentially terminal crisis for the Yeltsin régime as the 1996 elections approached. The privatisation minister, Anatoly Chubais, dreamt up a “loans for shares” scheme to raise funds by pledging the state’s largest industrial assets that including oil companies such as Yukos, Sibneft, and Lukoil in exchange for funding. Predictably, the loans were not paid back and the assets had to be sold. Just as had occurred with the smaller privatisations, when it came to auctioning the companies off, procedures would be subverted by insiders. The commanding heights of the Russian economy ended up in the possession of a few oligarchs, on the cheap. Their task had been made easier by the refusal of foreign investors to participate. Gennady Zyuganov and the new Communist Party of the Russian Federation [CPRF] had swept to victory in the 1995 Duma elections. at the World Economic Forum [WEF] at Davos, in February 1996, Zyuganov was feted as the future winner of the presidential elections later that year. He was, in addition, fully expected to fulfil his pledge to overturn the loans for shares privatisations and deprive the oligarchs of their ill-gotten gains.

In the event, Yeltsin won the election. Some argue that the structural differences between a two-horse presidential election and a multiparty election made all the difference (McFaul 1997: 10-14). However, allusions in the same analysis to campaign finance irregularities and media bias fail to give the correct weight to the intervention of the oligarchs. Boris Berezovsky, Vladimir Gusinsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and Vladimir Vinogradov among others organized their campaign for a Yeltsin win at the February 1996 Davos meeting. On his deathbed in London, in 2013, Berezovsky would repent his multiple sins and stated in no uncertain terms, in 1996 ‘we raped the media.’ The choice offered to the public in the presidential was essentially defined by the oligarchs, and Russian media chiefs became extremely wealthy in the process.

Putin didn’t do to the oligarchs what Zyuganov wanted to do, but he nevertheless set out to tame them at a meeting in July 2000, only two months after his inauguration as president. They were told to keep out of politics and to allow their resources to be used for the purposes of the state (Sakwa 2020: 93). Putin saw a use for the oligarchs. According to Pavlovsky, he disliked the Soviet system and thought:

‘…we were idiots… If we had made more money than the western capitalists, we could have just bought them up… It was a game and we lost, because we didn’t… give the capitalist predators on our side a chance to develop and devour the capitalist predators on theirs’ (Pavlovsky 2014: 56).

But one oligarch, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who had bought Yukos in the loans for shares scheme, stepped over Putin’s red lines. He not only openly acclaimed his neoliberal belief that the state should subjected to capitalists, but he brought in Westerners (Texan oilmen) to run the most important parts of what was Russia’s largest and most prestigious oil company: its production, technology and finance divisions. All the other oil sector bosses were outraged by his “un-Russian” methods of production. Khodorkovsky also incensed the most important member of the liberal faction in the Kremlin, Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, one of Putin’s coterie from St Petersburg, who had found Putin his first job in Moscow. Not only were Khodorkovsky’s tax minimisation schemes aggressive, but he bragged openly about his bribes to Duma officials who blocked legislative unfavourable to him. Ultimately, however, if Putin could go to war with Khodorkovsky and Yukos, it was because ‘they were seen by a wide range of Russian élite opinion as a foreign body and a threat’ (Gustafson 2012: 273). On issues of this importance, Putin only moved consensually.

Khodorkovsky’s eventual arrest on charges of fraud in October 2003, was a ground-shaking event that led to the exodus from the Kremlin of those liberals who were the remaining members of the so-called ‘Yeltsin family.’ Leading members of Putin’s coterie of St Peterburg liberals, Kudrin, German Gref and Dimitri Medvedev stayed on, however.

The arrest had an electrifying effect on all the other oil barons. Roman Abramovich who had planned to merge Sibneft with Yukos ‘made the sharpest turn… over the weekend of November 29-30 he suddenly announced that the merger was off’ (Gustafson 2012: 306-7). Vagit Alekperov cancelled Lukoil’s restructuring programme, in which he had sought to emulate Yukos’ production methods. The Ministry of Internal Affairs [MVD] in fact launched Operation Engerniia across all oil companies and fields, which sought to reverse the methods that Yukos’ Western management had introduced into oil field production. It was these methods, which overexploited oil fields, shortened their lives and endangered ultimate recovery, that had been loudly decried as “un-Russian.” Yukos’ competitors, however, had been forced to consider responding in kind as they began to lose market share. The MVD put a stop to that.

The period 2003-2006 was the low point for the liberal faction in the Kremlin and the high point for the so-called siloviki (the “men of power” from the FSB and the military) led by Nikolai Patrushev, another Putin colleague from St Petersburg, who replaced him as head of the FSB. There were the colour revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine, the Iraq war aftermath, and North Caucasus terrorism during that time which needed their attention, but they also had a free hand in settling the intra-élite feuds in the energy sector. As Putin reclaimed the commanding heights of the Russian economy for the state, two other members of his old coterie of St Petersburg siloviki became integral to the creation of Russia’s two “national champions,” vast corporations free of foreign influence, which would do the state’s bidding in the domestic economy. Igor Sechin at Rosneft absorbed most of the assets of Yukos and Sibneft, and, in the gas sector, Alexei Miller headed the giant Gazprom. Along with bringing all the regional governors into line, this completed Putin’s resurrection of the Russian state.

But having achieved the political objectives of his second presidency, which was nearing its end, Putin began to listen to Kudrin about the need to engage with the West and to push for Wordl Trade Organization [WTO] membership, with the aim of developing the economy. State power would be consolidated around the hydrocarbon sector and its national champions, but this needed to be leveraged in a programme of rapid diversification away from hydrocarbons for the economy as a whole.

So it was that the pendulum swung against the siloviki when on June 1, 2006, the General Prosecutor, who was in the forefront of the Yukos arrests, Vladimir Ustinov, was shunted sideways into the position of Minister of Justice. Many were moved to new positions. Even Patrushev was moved from the FSB to the post of secretary of the National Security Council, although that role would later assume greater importance with the Ukraine events of 2014.

Engaging with the West also meant making a determined effort to deal with the long standing sore of NATO expansion and the forward positioning of missile defence systems by the US in Eastern Europe. In May 2008, Medvedev became president. He launched his presidency with a charm offensive and major foreign policy speeches (Berlin, June 5, 2008; Evian, November 8, 2008; Helsinki, April 20, 2009), leading up the presentation of a proposed draft for a new European security architecture (November 29, 2009) that sought to establish an expanded Euro-Atlantic Community to include Russia, on shared terms with the West. With the name of “The Fourteen Points,”Medvedev’s draft European Security Treaty even had a Wilsonian internationalist flavour. After the August 2008 Georgian War under Bush II temporarily derailed the diplomatic flow, Obama’s inauguration as US president saw a “reset” in US-Russia relations in March 2009. Obama’s Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, however, remained sceptical and ultimately rejected Medvedev’s proposals in January 2010. Russia would get the consolation prize of joining the “Partnership for Peace,” like Ukraine and everybody else who were not actual NATO members.

NATO’s March 2011 Libyan bombing campaign, in which NATO exceeded the agreed terms of UNSC resolution 1973, angered Putin and is often seen as the point of no return in his relations with the West. But of substantially more concern to the Russian leadership was the European Union’s Third Energy Package (TEP) launched on 3 September 2009, which demanded the privatisation of the Russian gas industry to ‘secure a competitive and sustainable supply of energy to the economy and society’. The TEP began as an effort by the Lithuanian government to push Gazprom to divest assets under its jurisdiction, and clearly represented a direct threat to the core interests of the Russian state as Putin had defined them, in his first two terms as president. But all this was driven by the American dislike of state-owned energy suppliers, on which a clear statement was made in May 2006, following the gas shutdown to Ukraine in January, when the US Senate unanimously adopted a resolution calling on NATO to protect the energy security of its members and have it develop a diversification strategy. Senator Richard Lugar, in a strident speech prior to the NATO summit in Riga, Latvia, in November 2006, argued in favour of designating the manipulation of the energy supply as a ‘weapon’ that can activate Article 5 of the NATO treaty on common defence. NATO was thus viewed in Washington as the battering ram that would destroy states and allow the neoliberal programme of privatization to proceed untrammelled. Putin’s work to resurrect a Russian state leading in the creation of new collective international organisations challenging the Neoliberal Order (such as the Eurasian Economic Union [EEU], Collective Security Treaty Organisation [CSTO], Shanghai Cooperation Organisation [SCO], and BRICS] was anathema.

Taking effect on 3 March 2011, the TEP led to EU countries’ refusal to enter into long term contracts with Gazprom, and eventually to rising tensions with Russia over the spiralling cost of gas, as energy suppliers inevitably began to chase spot prices in a chaotic market. As EU-Russia energy relations collapsed, the United States saw an opportunity to rescue the ‘money-losing boondoggle’ that the fracking industry, a malinvestment born in the delusional era of the Federal Reserve’s zero-bound, had become. American administrations started coming down hard on Germany’s energy relations with Russia. As Merkel defended the building of the new Nord Stream II pipeline, her 2003 ringside ticket to the neoconservative ideology-fest was traded by Obama for a wiretap on her phone.

With these developments, Putin changed tack and informed Medvedev that he wouldn’t enjoy a second term as president. Patrushev at the National Security Council, Miller at Gazprom and Sergin at Rosneft pushed Putin to take the reins. They all saw the emerging national security threat posed by the United States interfering in Russian gas supplies to Europe and growing American interest in Ukraine, through which most of its gas to Europe flowed. They negotiated with Medvedev. If Medvedev agreed with a new policy of accelerated militarisation, despite the burden this would entail in a period of declining revenues resulting from declining oil and gas prices in the post-2008 financial crash recession, he could be prime minister. Medvedev agreed the terms the siloviki set. But he then quarrelled with Kudrin, who resigned as finance minister, who called the new military budget “insane.” Kudrin left government in 2011 with a raft of liberals that included the brains behind Putin’s PR machine, Vladislav Surkov and Gleb Pavlovsky, who had been committed to a gradual return of the state to its constitutional moorings. Likewise economist Igor Yurgens decamped. He had been committed like Kudrin to diversification away from hydrocarbons.

The 24 September 2011 so-called rokirovka (the “swap” or “castling” move), where Putin and Medvedev cynically swapped roles, delivered a shock to liberal élites. This period registered a low point in Putin’s popularity with fraud detected in the 2011 parliamentary elections, and Putin re-elected president in the 2012 election in which he set up webcams across Russia’s thousands of polling stations, to prove to a crowing Hillary Clinton that his election was free and fair. The OCSE nevertheless came out accusing Russian media of bias in the elections.

Rather than diversifying away from hydrocarbons, the new Putin régime would seek actively to diversify export avenues for Russian hydrocarbons. In October 2012, Miller received his marching orders to build the Power of Siberia pipeline, ahead of Xi Jinping’s March 2013 visit to Moscow that would take place not two weeks after the Chinese Communist Party leader’s inauguration as his country’s president. The actual $400bn sales contract for Gazprom’s gas supply to China would be signed in May 2014.

The new energy relationship with China would not come a moment too soon, as the Maidan revolution in Kiev in February 2014 put a right-wing anti-Russian party in power. These events threatened the prospect of keeping the Russian Black Sea fleet in place in Sebastopol. Russia had signed a lease with Ukraine’s previous elected president, Viktor Yanukovych, in 2017 for use of the base over a twenty-five year term, ending in 2042. But as Yanukovych had been overthrown unconstitutionally, there was no guarantee that the new Kiev régime would keep to the lease contract. For Putin, as much as keeping a Sebastopol presence had historic value, the real point of the Black Sea Fleet was to protect Russian state and commercial interests. At that time, this meant specifically protecting the prospects of building the South Stream Pipeline under the Black Sea to further diversify gas supply routes to Europe. As much as the vast majority of Crimeans wanted to be integrated into the Russia Federation and protected from the new anti-Russian Kiev régime, the Crimea action that was pushed by Patrushev and the siloviki in 2014 had a new urgency in the context of the energy policy at the core of the project of the reconstruction of the Russian state.

Indeed, Crimea was so important that, when Putin met Merkel on the margins of the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil, he proposed to regularise Crimea’s annexation by formally guaranteeing Ukraine’s territorial integrity (so, withdrawing support for the Donbass insurgency), granting Crimea special devolved powers and offer Ukraine a land-for-gas deal including a multi-billion-dollar compensation package for the loss of the rent it would have received from the lease of the Sevastopol base. However, the day that Putin flew back from Brazil, on 17 July, Malaysian airliner, flight MH 17, was downed over Ukraine. Merkel and the other European leaders, who were considering the land-for-gas deal, were rendered impotent by the deluge of sanctions that the United States demanded they impose on Russia following the airline disaster.

Then, by December 2014, it became clear that the EU wasn’t going to allow Bulgaria to sign a deal to build its portion of the South Steam project in the Black Sea, which Brussels said didn’t conform with the TEP. It was then that Putin made a state visit to Turkey to agree the building of Turk Stream alongside the existing, but inadequate, Blue Steam. But it would be two years before construction eventually started, during which period a series of highly charged events embroiled Russia deeply in Turkish and Middle Eastern politics. With the United States supporting a Kurdish client state in the making on Turkey’s southern borders, Putin exploited Obama’s reluctance to pursue régime change in Damascus, in view of his negotiations with Iran on nuclear weapons (ongoing since the famous September 2013 phone call with Iranian president Rouhani). Putin saw an opportunity to install Russia in Syria. Despite the Crimea episode, Russia was still cooperating with America’s War on Terror project in and around Afghanistan. On being asked by Assad of Syria and Suleimani of Iran for military help against a two year old insurgency, Putin volunteered Russia for a new role in the context of the War on terror, to fight Islamic State in Syria. In September 2015, Russia garrisoned its old naval base at Tartus and built an airbase at Khmeimim, north of Tartus, an hour’s drive from Turkey.

Within two months of these events, the Turkish air force had shot down a Russian fighter jet. Putin, meanwhile, retaliated with economic sanctions on Turkey and a suspension of Turk Stream. The argument that erupted about whether the Russian jet had violated Turkish airspace (an argument that was never resolved) begged the question as to why Russian jets would spend so much time and effort buzzing the Turkish border in that period, begging for one to be shot down, if the idea of the Russian presence in Syria was to fight Islamic State. The answer to this conundrum came when Russia shipped an S-400 anti-aircraft system to Khmeimim, which the Americans would normally have actively tried to prevent. It was wholly unnecessary for the purpose of fighting jihadis. Be that as it may, in March 2016, with a well defended airbase now established south of the Turkish border, Putin could order a reduction of troops numbers there, in an effort to rebalance Russia’s relationships between Iran and Saudi Arabia. This was planned with an eye to enlarging OPEC to an OPEC+ format in the future in order to address the depressed energy markets at the time with Saudi Arabia’s help. In the event, relations with Erdoğan were repaired and Turk Steam built in record time, with Russia now joining Turkey in the construction of a major gas hub in Thrace, besides delivering Turkey’s first nuclear power station at Akkuyu.

Putin’s goal of resurrecting the Russian state was entirely predicated on domestic and international energy policy. If the Crimean move was intended to underwrite this policy, the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine was in essence intended to protect Crimea from what both Russian signals intelligence and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) detected as the start of a major Ukrainian campaign to take Donbass and retake Crimea. This explains Putin’s continuous attempts at a negotiated resolution, even though this made him look weak in the eyes of both NATO and Russian nationalists. The acquisition of territory in Ukraine was never a policy goal and still isn’t, although the failure of negotiations has now led to a policy of creating a buffer against NATO by laying waste to Ukraine.

II. 3 How and why US foreign policy élites founded US global hegemony on American coercive dominance of Europe and why a NATO defeat in Ukraine threatens US global hegemony:

With the failure of Putin’s negotiating strategy, and the demise of the role of private military contractors in the Ukraine War, the Russian Ministry of Defence has gradually gained overall control on military strategy in Ukraine. Its consolidation of command and control systems over the battlefield, its acquisition of new communication systems and the speeding up of the programme of military satellite launches, and its new mobilisation all come as Ukraine’s own “total” mobilisation of 22 June cries of desperation. There is little prospect of Russian defences being breached and little prospect either of attrition rates amongst attackers being reduced.

But as the gruesome prospect looms that Senator Lindsey Graham held out for Ukraine that it ‘will fight this war to the last person,’ changes are afoot. NATO already tables plans for Polish and other east European forces to join the war and take the place of the Ukrainians, as the counteroffensive fails. But just as Ukraine’s human resources were ultimately no match for Russian resources, the same will apply to those alternative proxies. If NATO resorts to such a strategy instead of sitting down and negotiating peace, it will be taking the war closer and closer to the heart of Europe with no guarantee of success. At this point, General Vad’s warnings come to mind about the demonstration effects on NATO cohesion of defeat, even as a “surge strategy” is being re-treaded from an Afghan/Iraqi model used, disastrously in every case, as political plaster for military disaster.

One has to remember that US hegemony in Europe was maintained not only by riding roughshod over Russia and Russian sensibilities, but over the West European nations and their sensibilities as well. Remember the Iraq war demonstrations? The popular will in Europe would never be allowed to interfere with empire. But it all started with three wars that were instigated in Yugoslavia in the wake of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in which the formula for American dominance of Europe would be worked out. These were essentially intended to counter Germany’s resurgence, the rise of the EU, and the prospective common currency for EU members – the EURO.

The first conflict began because of German policy on Croatia. Not satisfied with absorbing the DDR, Kohl and his foreign minister, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, sought to create a client state in Croatia through their unilateral recognition of its independence in 1992. This was done without first resolving or protecting the status of the local Serbian community, which in fact had the theoretical protection of the Yugoslav constitution, as a legal “nation” within the Croatian state. Carelessly, or perhaps intentionally, Germany’s move created the conditions for their ethnic cleansing by Croatian leader Franjo Tudjman.

Suddenly upstaged by these events the Clinton administration resolved to impose the United States as ultimate arbiter on the Yugoslav question, by forcing Bosnian leader, Alija Izetbegovic, against his will, to declare independence for a Muslim state in Bosnia. Incredibly, this would be erected over Coat and Serb communities that together would form the majority in the new entity and would lose the protection of the Yugoslav constitution. The Bosnian War that erupted in 1995 was thus intentional policy on the part of the United States. It should be clearly understood that this decision was taken in the context of a Clinton administration that had already decided on NATO expansion. William Perry, and the Department of Defense generally, were cautious, voicing concerns about Russian opposition. But Richard Holbrooke, Ambassador to Germany, soon after his appointment as assistant secretary of state for Europe in September 1994, brushed this aside. He ‘told a stunned group from the Pentagon the president had stated his support for enlargement and that it was up to them [sic] to act on it’ (Goldgeier 1999: 20). Holbrooke’s paper ‘America, A European Power’, argued that ‘the West must expand to central Europe as fast as possible in fact as well as in spirit, and the United States is ready to lead the way,’ with NATO as the ‘central security pillar’ of the new European architecture (Holbrooke1995: 42).

Samuel Huntington would write that in ‘… the post-Cold War world, NATO is the security organization of Western civilization. With the Cold War over, NATO has one central and compelling purpose: to insure that it remains over by preventing the reimposition of Russian political and military control in Central Europe’ (Huntington 1996: 161). Holbrooke was no stranger to Huntington, whom he knew from their service in the Democratic administration of Jimmy Carter. Carter was the Southern Baptist peanut farmer who, with the help of his National Security Adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski (Huntington’s mentor), had called a halt to détente with the Soviet Union, started the US involvement in Afghanistan, and developed a new nuclear doctrine (Nuclear utilization target selection [NUTS]) committed to fight and win a nuclear war (Amadae 2015: 105–111). For Huntington, politics in the new post-Cold War era would be driven by civilizational conflict. Indeed, Peter Gowan tells us how Huntington’s “clash of civilizations” narrative would take over the justification for the Bosnian war. The ‘… war [became] a policy success for the US, which took control of events in the Yugoslav theatre and very successfully polarized European politics around those who supported the “Bosnian nation” versus those who supported a drive for “Greater Serbia”…’ (Gowan 1999: 95).

Having thus successfully polarised political perceptions along a West European-Slavic divide in the Bosnian War, in which a helpless Russia would automatically be “on the wrong side,” the United States could now launch a new war based on the new narrative. It would take Europe into a war against Serbia launched to push forward the Anglo-American sphere of influence on the European continent as far as possible, ahead of the implementation by the EU of the EURO, given that Russia, in the throes of its 1998 financial default, was totally powerless to prevent it.

The Serbian-Kosovo (or Balkan) War was a surprise to everyone except the United States. Some Kosovans had become restive and the Kosovo Liberation Army [KLA] had become active. There had originally been an agreement between the US and Serbia to publicly brand the KLA a terrorist organisation, and for Slobodan Milosevic, accordingly, to launch a counter-insurgency campaign in March 1998, which would be accompanied by an offer of provincial autonomy from Serbia to the Kosovans . By October 1998, however, Madeleine Albright had turned the tables on this arrangement by issuing a document outlining terms for peace negotiations between the Kosovan parties, with a plan for that political process to be supervised by a new NATO-led military “compliance” force, in other words there would be a US occupation of Kosovo. This was designed to produce outrage in Belgrade. If action had been taken through the diplomatic channels afforded by the NATO–Russia Permanent Joint Council (NRPJC), war with Serbia could, even then, have been avoided. Instead, the scene was set for reinterpreting the Serbian counter-insurgency as ethnic cleansing and declaring a “humanitarian disaster,” which would now be met with a NATO bombing campaign.

Gerhard Schröder, who succeeded Kohl in 1998 and who would later try to take his revenge by trying in vain to stay out of the Iraq War, was railroaded by Bill Clinton into joining the “military humanitarian intervention.” His coalition partner, Joschka Fischer from the Green Party, would be forced to insist to outraged members of his pacifist party that Serbian repression of the Kosovars would be ‘another Auschwitz.’ Anyone who opposed NATO intervention, he shouted, would be responsible for a second holocaust.

Gowan summarises the US rationale: ‘A military attack on Yugoslavia by the whole NATO alliance would, of course, have enormous pan-European political consequences.. [and] decisively consolidate US leadership in Europe. Success outside the framework of UN Security Council permission would [rule out]… a Russian veto. And it would seal the unity of the alliance against a background where the launch of the EURO – an event potentially of global political significance – could pull it apart.’

With Hungary and Turkey already outliers in the NATO alliance, and France muttering under its breath, a defeat in Ukraine with serious blowback on German politics would begin an unravelling of the NATO alliance and thus of US hegemony. If a “surge” is resorted to, as the Ukrainian state collapses, this would have to involve primarily Poland, given that other east European contenders have much smaller populations. But if this means either that German troops need to be stationed in the Baltics, or if Poland entered this escalation with its well-known designs on Galicia as its own rationale, European politics would enter a period of severe turmoil. The effects of the Ukrainian war would move full square into the empire’s heartland.

[Ref: Prt 10 Post-Script 10; info@globalshiffft.com; © 2023]

Leave a comment